Determining if the atmospheric release from a pressure relief device (PSD) is safe is good engineering practice and a requirement defined by OSHA and ASME. Relief devices that are not connected to a closed relief system (flare header, knock out pot, etc.) should have tailpipes to direct the relieving stream to a safe area. An engineer can use readily available tools to preliminarily screen most atmospheric releases to determine if a more detailed quantitative evaluation is needed to generate a relief design guideline. The combination of preliminary screening, semi-quantitative evaluation and more detailed quantitative evaluation can be used to streamline the overall review process.

Screening

Initial screening of each valve should be performed to categorize the level of risk. This involves a review of the existing PSD sizing calculations and existing hazards evaluation reports/recommendations to classify each device into one of the following categories based on the nature of the fluid discharged:

- Relief devices that simply need to be piped so that discharge does not have the potential to impinge personnel in its path or inhibit an operator from performing a function in an emergency. Examples of this are low pressure steam releases or thermal cooling water reliefs.

- Relief devices that may have a slightly higher level of safety concern and will require some qualitative evaluation to define a specific relief guideline. Examples of this are a release of an asphyxiant or a saturated vapor that may condense.

- Relief devices that will require more detailed quantitative analysis to generate a relief guideline. Examples of this are flammable vapors, toxic vapors, vapors heavier than air, and vapors that may cause an offsite odor issue.

- Relief devices that are special cases. For example, a relief device that has been sized for vapor release but may have situations that could release a flammable liquid, a 2-phase mixture, or solids. These will require special design considerations. Releases of liquids or solids to the atmosphere are not acceptable and will require special design (i.e. containment or safety instrumentation to eliminate a credible release scenario).

The screening step determines which valves should be carried further into a quantitative evaluation so that a relief guideline can be established. First and foremost, a conservative approach should be taken in the screening step to minimize the possibility that unsafe atmospheric PSD discharge could escape detection and not be flagged for further, more detailed, quantitative evaluation by the engineering team.

Semi-Quantitative Analysis

Preliminary calculations are performed to compare data to key process parameters that allow for a more detailed definition of the potential risk associated with the release and determine if a more detailed quantitative evaluation (such as dispersion modeling) should be performed. The key variables include the following:

- Adequate mixing – API STD 521 6thAPI STD 521 6th edition 5.8 provides guidelines to determine if a relief device discharge to atmosphere is acceptable based on the mixing effects at the discharge. To semi-quantitatively determine if a release is acceptable, the following criteria must be met:

-

- Exit velocity should be greater than 100 ft/sec. Studies have shown that the hazard of flammable concentrations existing below the point of discharge is negligible as long as the discharge velocity is sufficiently high. The evaluation should be done at various valve capacities (e.g. 25%, 50% and 100% of the rating) since there is a potential that the valve discharge rate may be lower than the actual rated capacity of the valve.

- Vapor MW should be less than 80

- Relief temperature should be at or below the atmospheric temperature.

If any of these criteria are not met, it should be assumed that adequate mixing may not exist and a potential for an unacceptable concentration at ground-level may be present.

- Vapor density – if the vapor density is heavier than air, the vapor cloud may migrate to ground level and pose a hazard. Additional analysis is needed to determine if the ground-level concentration could be flammable or toxic.

- Vapor Reynolds Number (Nre) – if the vapor Nre > 1.54 * 104* (ρj/ρ∞) , per API STD 521 6th edition § 5.8.2.2

ρj = density of gas at the vent outlet

ρ∞ = density of the air

then the jet momentum forces of release are usually dominant. Else, the jet entrainment of air is limited, and flammable mixtures can possibly occur at grade or downwind. Additional analysis is needed to determine if the ground-level concentration could be flammable or toxic.

Note: The above equation may not be valid for jet velocity < 40 ft/s (12m/s) or jet-wind velocity ratio < 10.

- Potential for mist formation – the potential for mist formation to occur exists if the relief stream dew point is above the minimum ambient temperature at the site. A design that includes a knockout drum or scrubber should be installed in relief lines to separate and remove liquid droplets from the discharge.

- Maximum ground-level concentration (flammability and toxicity) – a preliminary screening calculation to determine the maximum estimated concentration at grade (Cmax) can be done to determine if further dispersion modeling should be performed. This information can be compared to the lower explosive limit (LEL) for flammable vapors (is Cmax greater than 25% of the LEL?) and to applicable exposure limits for toxic vapors (is Cmax close to the IDLH or TLV for that compound?). For example, a highly flammable material released that is above the LEL at the release point should be evaluated for the potential to reach >25% of the LEL at grade.

Note: One reference that provides a screening equation for Cmax is “Consequence Analysis of Atmospheric Discharge from Pressure Relief Devices, Qualitative and Quantitative Safety Screening” (Burgess, John P.E., Smith, Dustin P.E., Smith & Burgess Process Safety Consulting).

- Asphyxiant hazard – if an asphyxiant is discharged and the vapor release is heavier than air, additional evaluation may be needed, depending on the location of the relief device, to determine if there is a potential for buildup or re-entrainment of the vapors in occupied spaces.

Again, a conservative approach should be taken in the semi-quantitative analysis. Borderline acceptability of the above parameters should be considered for further modeling to ensure that the potential risk is accurately defined.

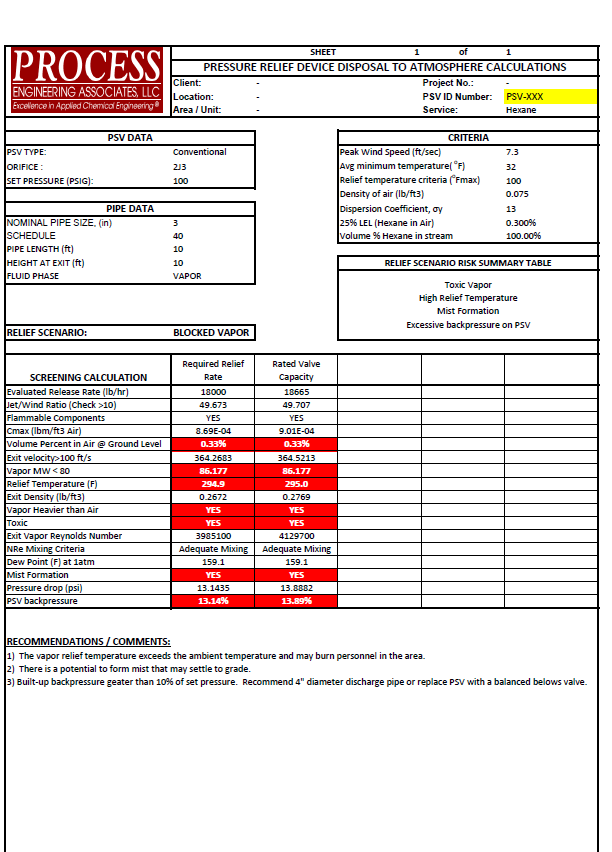

An example summary of the screening and preliminary semi-quantitative analysis is presented in the below summary table for a PSV releasing hexane.

As a result of this semi-quantitative analysis, each valve can be classified into a specific risk category. Depending on the risks, you can either (1) define an atmospheric relief guideline for the valve so that the PSD design can be completed or (2) determine that a more detailed quantitative analysis (e.g. dispersion modeling) should be performed to better understand the potential risk.

Detailed Quantitative Analysis

Results of the screening and preliminary semi-quantitative analysis may indicate that additional analysis (such as detailed dispersion modeling) is required to more specifically define the potential release pattern and level of risk associated with the vapor release such that a specific guideline can be established for the design of the tailpipe.

One method that is widely used to model these types of releases is ALOHA®. ALOHA® is a hazards modeling program that can define potential threat zones for chemical releases and can be used for flammable vapors, toxic vapors, BLEVEs (boiling liquid expansion vapor explosions), jet fires, pool fires, and vapor cloud explosions. This software package is from the CAMEO® Software Suite and can be downloaded for free at https://www.epa.gov/cameo.

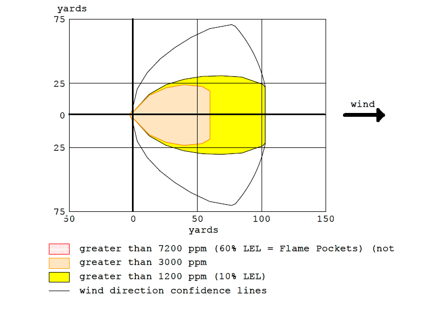

In the example above, ALOHA® was used to define the potential threat zones for the release of hexane from the PSD.

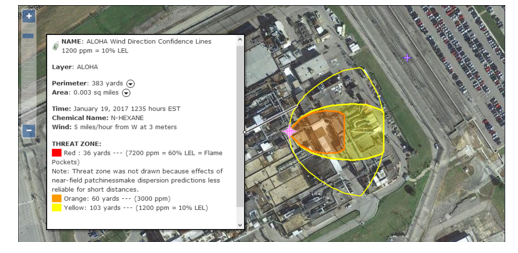

Using MARPLOT®, also a software program in the CAMEO Software Suite, the ALOHA threat zone estimate can be displayed on the map of the facility to graphically display the potential impact and better prepare for the chemical release.

Conclusion

An engineer can use readily available tools to screen most atmospheric release PSDs to define a specific relief guideline for that PSD. The evaluation should include both a qualitative screening and, as needed, more detailed quantitative methods to streamline the review and develop documentation that proves the discharge configuration is safe.